Understanding the Portuguese Legal Framework for Divorce

Portugal’s legal system for divorce is rooted in the Civil Code of Portugal, which provides the foundational framework for matrimonial dissolutions. Divorce proceedings can be broadly classified into two categories: consensual divorce, also known as divorce by mutual consent, and contested divorce. Each type follows specific procedures, requiring different levels of documentation and legal intervention.

Divorce by Mutual Consent

Divorce by mutual consent is the simplest and most expedient method in Portugal, often handled by civil registries. This method requires both parties to agree on key elements such as property division, alimony, and issues regarding children. Translators should be familiar with terms like “consensual divorce” (divórcio por mútuo consentimento) and “settlement agreement” (acordo de regulação das responsabilidades parentais).

The process initiates with an application filed jointly by both spouses, which includes a detailed plan for shared responsibilities. Translators should ensure accuracy and clarity in translating these documents, particularly any agreement on child support (pensão de alimentos) and visitation rights (direito de visita).

Contested Divorce Proceedings

In instances where mutual consent cannot be reached, a contested divorce ensues, requiring involvement of the Family and Minors Court (Tribunal de Família e Menores). Translators involved in contested divorces should be versed in complex legal terminology and the procedural nuances of Portugal’s judicial system.

Contested divorce petitions often involve accusations of misconduct like adultery (adultério) or abandonment (abandono do lar). These claims can significantly impact the outcome, making precise translation of court filings and evidence crucial. Translators should pay special attention to legal jargon particular to Portuguese family law, such as “fault divorce” (divórcio com culpa) and “irretrievable breakdown” (rutura definitiva do casamento).

Custody and Child Support Considerations

Custody arrangements in Portugal, known as parental responsibilities, prioritize children’s welfare, aligned with EU regulations. Translators should translate terms like “joint custody” (guarda conjunta) and “custodial parent” (progenitor guardião) in a manner that aligns with both legal standards and cultural context.

Documents related to parental responsibilities and child support require careful consideration of language nuance, as any ambiguity may lead to misinterpretation. It’s crucial for translators to maintain the original intent, especially in agreements detailing financial obligations or parental duties.

Division of Marital Property

In Portugal, property division follows a community property regime unless otherwise stipulated by a premarital agreement. Legal translators must be adept at terms like “community property” (comunhão de adquiridos) and “separate property” (bens próprios). These concepts affect how assets and debts are divided; thus, precision in translation ensures adherence to the law and equitable outcomes.

Alimony and Spousal Support

Alimony, or spousal support in Portugal, may be requested during the divorce proceedings or following the final decree. Translators should be familiar with the term “alimony” (pensão de alimentos) and the criteria for its award, which include the financial status of each party and the marriage’s impact on their earning potential.

Legal Representation and Mediation

Both parties in a divorce may opt for legal representation to navigate complex proceedings. However, mediation serves as a pivotal alternative dispute resolution method. Translators must accurately convey terms such as “legal counsel” (advogado) and “mediation agreement” (acordo de mediação), ensuring clear communication during negotiations.

Translators should be prepared to facilitate smooth communication during mediation sessions, making sure both cultural nuances and legal particulars are appropriately addressed. This role often demands confidentiality and neutrality, aiding parties in reaching amicable settlements.

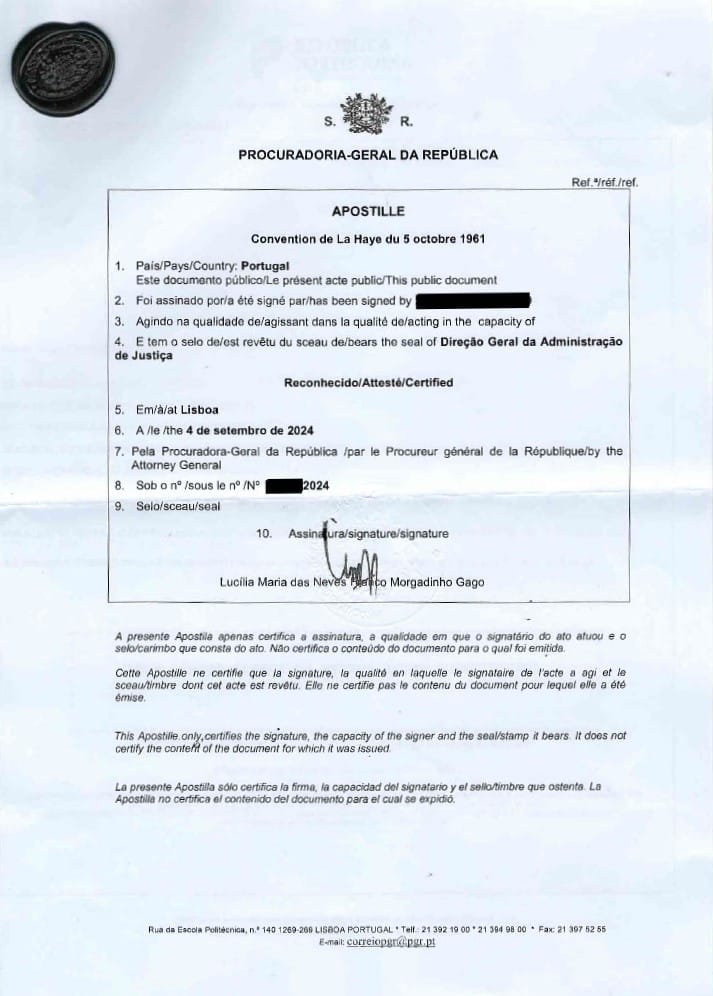

Translation Accuracy and Certification

For documents to be legally recognized, translations often require certification, especially those submitted in court or civil registries. Translators should understand certification processes (certificação de tradução) and the necessity for notarization by Portuguese notaries (notários).

Legal documents must be translated with both linguistic precision and legal understanding. The translator’s role is not just to convert language but to ensure that legal concepts are correctly interpreted and localized to meet Portuguese judicial requirements.

Ethical Considerations for Legal Translators

Working on divorce cases, translators must adhere to strict ethical guidelines, especially regarding confidentiality and impartiality. They must balance professional obligations with sensitivity to the personal nature of divorce proceedings.

Understanding privacy laws and maintaining confidentiality is paramount, as well as upholding impartiality to avoid any bias influencing the translation work. This level of professionalism ensures translators provide fair and unbiased assistance throughout the complex emotional landscape of divorce litigation.

Staying Updated on Legal Changes

Portuguese law, like all legal systems, evolves. Translators should remain informed about any amendments to divorce laws or related legal reforms. Continuing education and involvement in professional translation networks can aid translators in staying current with legal terminology and procedural changes, thus enhancing their service quality.

For translators, this commitment to ongoing learning and adaptation ensures that their translations reflect the most current legal practices, thereby upholding the integrity of the legal process and supporting clients in achieving just outcomes in their divorce proceedings.