Portuguese divorce law, rooted in Roman legal traditions and shaped by contemporary legislative reforms, is a complex yet methodically arranged system. For translators working with legal documents, a deep understanding of this area is invaluable. Translators must be well-versed not only in the language but also in the intricate details of the legal processes involved. This ensures accuracy and cultural appropriateness, vital for clear communication among parties involved in divorce proceedings.

Divorce in Portugal can occur under three primary circumstances: mutual consent (divórcio por mútuo consentimento), no-fault (divórcio sem consentimento do outro cônjuge pacificamente), or fault-based (divórcio litigioso). These pathways are enshrined in the Portuguese Civil Code and have specific requirements and implications.

In cases of mutual consent, spouses agree jointly on the terms of their divorce, covering important issues like child custody, alimony, and division of assets. This type of divorce is processed through the conservatória do registo civil, or the civil registry office, which can simplify and shorten the proceedings. Documents needed for this process include a comprehensive written agreement on the aforementioned issues and proof of each spouse’s identification.

When one spouse cannot agree to a divorce, the law provides for a no-fault divorce. The requesting spouse doesn’t need to prove the other party’s fault, although a separation for one year must be demonstrated. The Code stipulates that irreparable breakdown of the marriage is a valid cause. Here, translators must pay keen attention to the language indicating separation, ensuring it aligns with legal definitions in both cultural contexts.

For fault-based divorces, serious offenses—such as infidelity, domestic abuse, or criminal convictions—that make the marriage untenable are required to be proven. The language in these documents tends to be very detailed and specific, demanding high levels of accuracy and neutrality from the translator.

Central to translation is the understanding of the legal terminology used in divorce proceedings. For example, the term “pensão de alimentos” is commonly misunderstood; it refers not only to child support but also to spousal support. This highlights the need for precise translation to ensure that legal obligations are accurately communicated.

Translators must be agile in navigating family law within the Portuguese jurisdiction; article-specific references, such as those in the Civil Code, provide the legal backbone. Article 1773 et seq. governs divorce types and procedures, embodying the legislative intent. Translators should be familiar with these nuances to convey legal concepts correctly.

Additionally, cultural competence is paramount. Portuguese legal traditions might differ drastically from those in the source language’s jurisdiction, affecting how certain legal concepts are understood and translated. Divorce in Portugal can also be influenced by Catholic values, impacting how legal terms are interpreted and applied.

The division of marital property under Portuguese law follows a community property regime, unless pre-agreed upon otherwise. This entails that translators must have a deep understanding of property rights terminology in both Portuguese and the source language. Terms like “bens próprios” (individual property) and “bens comuns” (community property) are critical in drafting settlement agreements.

Child custody arrangements, known as “guarda de menores,” are contingent upon the child’s best interest, encompassing a wide array of factors. Translators should be adept in both understanding and translating psychological and evaluative reports that influence custody decisions. This requires familiarity with not only legal jargon but also psychological and sociological terms.

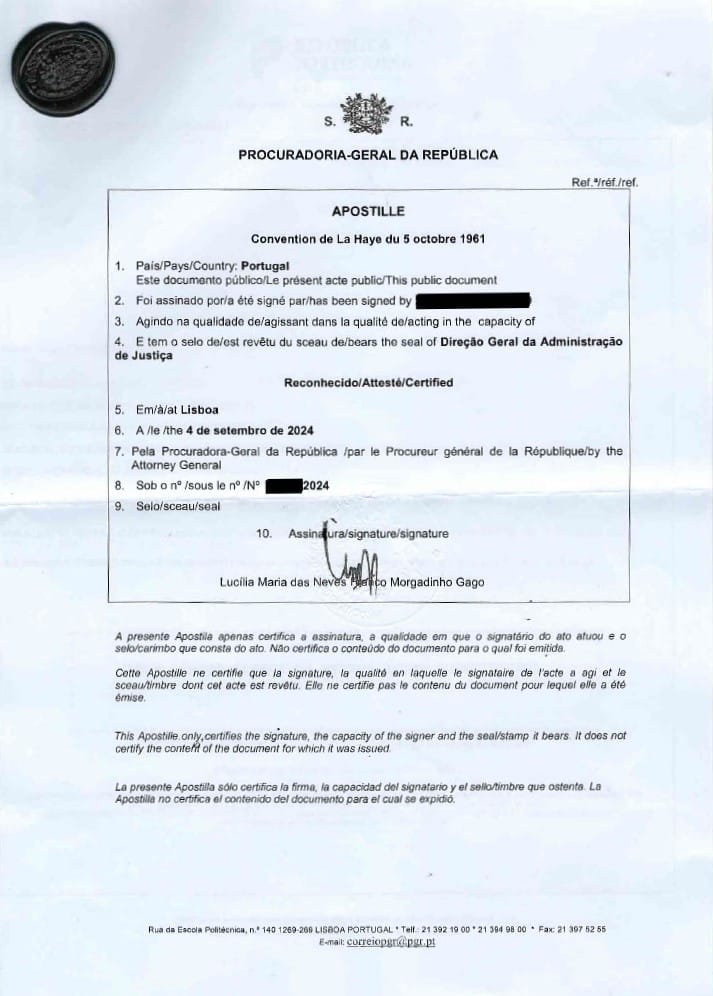

Moreover, translators must be diligent with the procedural aspects of divorce law. Portugal requires specific forms and applications, each with distinctive formats and language. Accurate translation ensures compliance and aids in expediting the legal process. Translators need to ensure that plea formats, citations, and official letters comply with the procedural norms of both the Portuguese legal system and the foreign client’s jurisdiction.

Alongside linguistic skills, translators involved in Portuguese divorce law need superior research skills to stay updated with continual legislative changes. Portugal, being part of the European Union, frequently updates its laws to better align with EU directives, affecting family law norms.

Technology, too, plays a significant role. Translation memory tools can assist in maintaining consistency in terminology across different documents. However, translators should exercise caution, as rigid reliance on automated tools can overlook context-specific nuances crucial in legal translations.

Understanding non-legal elements that might influence divorce proceedings, such as economic circumstances, changes in custody regulations, or cross-border marriage complications, enriches the translator’s capability to handle documents holistically. Given Portugal’s geographic and socio-political climate, these factors can be decisive in the context of international divorces.

To conclude, tackling Portuguese divorce law as a translator requires an astute blend of legal, linguistic, and cultural competencies. Translators must maintain a balance between fidelity to the source text and the accurate conveyance of legal principles across cultural boundaries to facilitate seamless legal proceedings.