Portuguese Divorce Law: Key Concepts for Accurate English Translation

Divorce law in Portugal has evolved considerably over the years, reflecting changes in societal norms and attitudes towards marriage and family. Understanding the nuances of Portuguese divorce law is essential for accurately translating legal documents into English. This involves familiarizing oneself with the relevant legal terminology, different divorce processes, grounds for divorce, and related family law issues. The translation of legal texts demands precision and contextual understanding to ensure both legal professionals and their clients can rely on the translated documentation.

1. Legal Terminology in Portuguese Divorce Law

Translating legal terms requires more than a basic dictionary. Portuguese divorce law is framed within the broader context of Portuguese Civil Law. Key terms include “divórcio” (divorce), “separação de facto” (de facto separation), and “cônjuges” (spouses). Precise translation of these terms is crucial, as misinterpretation can lead to misunderstandings.

“Regime de bens” refers to the property regime between spouses, an important concept, as it affects asset division post-divorce. In English, this translates to “matrimonial property regime.” Careful attention must be paid to ensure terms such as “guarda” (custody) and “alimentos” (alimony or child support) are correctly contextualized.

2. Types of Divorce: Consensual vs. Litigious

Portuguese law distinguishes between two primary types of divorce: consensual and litigious. A “divórcio por mútuo consentimento” (divorce by mutual consent) is comparable to an uncontested divorce. It is often straightforward, requiring both parties to agree on key issues, thereby streamlining the process.

In contrast, a “divórcio litigioso” (litigious divorce) arises when spouses cannot reach such agreements. This mirrors a contested divorce in English legal systems. Translators must understand the procedural differences, as documents and discussions will vary greatly between these types.

3. Grounds for Divorce in Portugal

Since legislative reforms in 2008, the concept of fault-based divorce has been largely abolished in Portugal, aligning it more closely with no-fault divorce concepts common in many English-speaking countries. However, translators should be aware of exceptions and historical contexts when dealing with older documents.

Grounds for divorce now primarily include de facto separation for at least one year, alteration in the spouse’s mental faculties that compromise life together, and absence of common life, among others. Translating these grounds requires knowledge of specific legal implications and cultural nuances that might not directly correlate with the English legal system.

4. Asset Division and Property Regimes

In divorce proceedings, understanding the matrimonial property regime is pivotal. Portugal recognizes several regimes, including “comunhão de adquiridos” (community of acquired property), “separação de bens” (separation of property), and “comunhão geral de bens” (universal community of property). These affect how assets are divided upon divorce.

Translating these terms into English involves understanding the equivalent concepts in common law systems, such as community property and equitable distribution, while considering the mandatory rules under Portuguese law.

5. Child Custody and Support

Custody issues are referred to as “regulação do exercício das responsabilidades parentais” (regulation of parental responsibilities). This term reflects the Portuguese emphasis on co-parenting post-divorce. In translation, clarity is vital to depict accurately the legal expectations laid upon parents.

Additionally, “pensão de alimentos” (child support payments) must be consistently and clearly translated to ensure both obligations and entitlements are understood. Translators should maintain awareness of distinctions between legal obligations in Portuguese and English contexts.

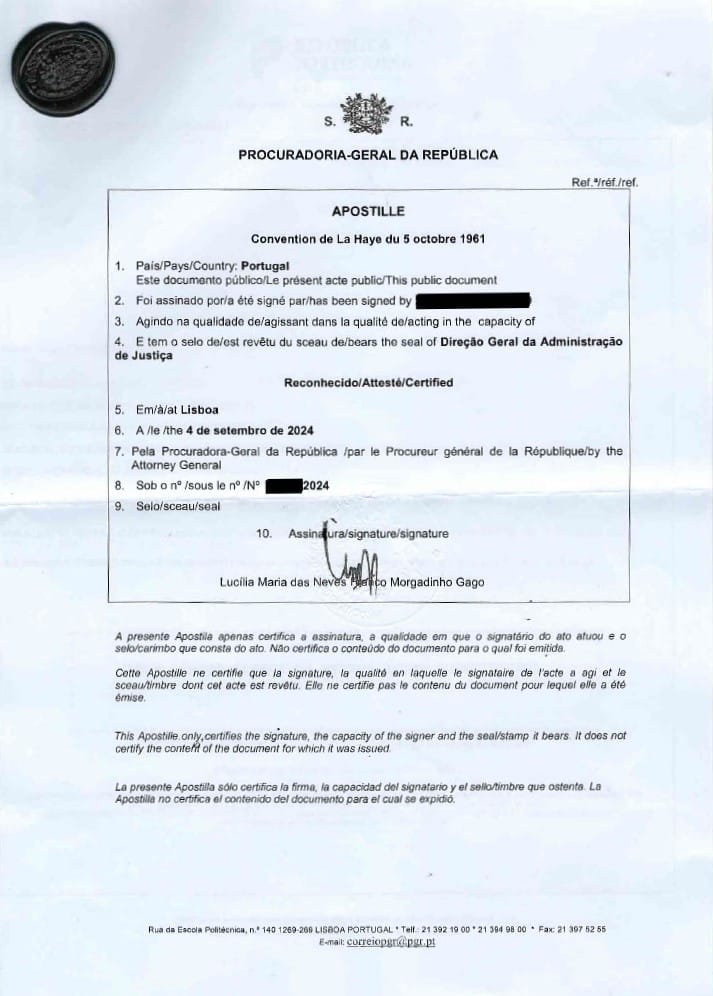

6. Procedural Aspects and Documentation

Translators must be familiar with the bureaucratic and procedural elements of the divorce process in Portugal. This encompasses filings in Conservatórias or family courts and understanding documents such as “petição inicial” (initial petition) and “acordo de regulação das responsabilidades parentais” (parental responsibilities agreement).

Translators should grasp the importance of personalization in translations. Original phrasing, tone, and juridical precision must carry through to English while adapting to the expectations of an English-speaking legal environment.

7. Cultural Sensitivities and Implications

Understanding cultural contexts is crucial. Portuguese law and society prioritize the family unit, affecting how divorce is approached in legal practice. This cultural nuance can influence how terms are received and should be carefully considered in translation to preserve meaning while bridging legal cultural divides.

In summary, translating Portuguese divorce law into English requires meticulous attention to legal detail, procedural specifics, and social context. Translations must capture the essence of the original documents while adapting them to fit the legal framework and expectations of a different legal system. This process ensures that translated documents retain their legal validity and comprehensibility for English-speaking legal professionals and clients. Each concept and term must be carefully analyzed to mitigate the risk of misinterpretation and to facilitate smooth cross-cultural legal transactions.