Understanding the nuances of legal terminology is crucial when dealing with international jurisdictions, particularly in divorce proceedings. The translation of Portuguese divorce terms into English requires not only linguistic proficiency but also a deep understanding of the cultural and legal contexts. This elaborate guide seeks to elucidate key Portuguese divorce terms for smooth and accurate English translation.

Among the frequently encountered terms is “Divórcio,” which straightforwardly translates to “Divorce” in English. However, understanding the types of divorces under Portuguese law can aid in refined translations. Portuguese law primarily recognizes two types: “Divórcio sem Consentimento do Outro Cônjuge” (Divorce without the other spouse’s consent) and “Divórcio por Mútuo Consentimento” (Divorce by mutual consent).

“Divórcio por Mútuo Consentimento” is often a less contentious procedure, akin to an uncontested divorce in the United States. Translation professionals should ensure that mutual agreements, captured by terms such as “Acordo de Regulação do Exercício das Responsabilidades Parentais” (Agreement on the regulation of the exercise of parental responsibilities), are correctly interpreted to reflect the consensual nature of these proceedings.

The term “Guarda dos Filhos” stands for “Child Custody.” This is divided into several categories, such as “Guarda Conjunta” (Joint Custody), and “Guarda Única” (Sole Custody). In translating these terms, one must also consider “Responsabilidades Parentais,” which translates to “Parental Responsibilities,” encompassing decisions regarding the child’s welfare, education, and religious upbringing. These are critical terms that often appear in documentation related to custody arrangements and must be translated with their full implications in mind.

“Patrimônio Conjugal” refers to “Marital Property.” In Portugal, unless a prenuptial agreement states otherwise, couples are usually subject to the “Regime de Comunhão de Adquiridos” (Acquired Community Property System). This system involves the sharing of assets acquired during the marriage. Knowledge of these property regimes is essential when translating agreements and court rulings related to asset division.

Another important term is “Pensão de Alimentos,” the Portuguese equivalent of “Alimony or Spousal Support.” The nuances in determining these payments, such as the length of the marriage and each spouse’s financial status, reflect similarly in both Portuguese and Anglo-American law. Precision is crucial here; translating the specifics of spousal support agreements requires attention to legal terminology and economic implications.

In matters of child support, “Pensão de Alimentos para os Filhos” (Child Maintenance) takes precedence. Typically, the court sets this based on various factors like the child’s needs and the parents’ financial capacity. Translators need to ensure that such details are accurately depicted in English, maintaining the monetary and legal essence of the agreements.

When addressing terms like “Tribunal de Família e Menores” (Family and Minors Court), it’s vital to understand the court’s jurisdiction and function within the Portuguese legal system. The Family and Minors Court handles cases related to divorce, child custody, and adoptions. Accurate translation requires awareness of the systematic and administrative differences between the Portuguese and other English-speaking legal systems.

Furthermore, documents may reference “Controlo Jurisdicional das Relações Paternais” (Judicial Control of Parental Relations), reflecting the court’s supervisory role in ensuring parental responsibilities are fulfilled post-divorce. This concept is crucial for English-speaking recipients to understand the extent of legal oversight in family matters.

The translation of “Mediação Familiar” (Family Mediation) should emphasize the role of mediation as a non-confrontational means of resolving disputes outside of court. In Portugal, this often involves a “Mediador Familiar” (Family Mediator) guiding the discussions. Ensuring that these mediation-related terms are translated with sensitivity to alternative judicial practices aids in promoting mutual understanding.

“Partilha de Bens” translates to “Asset Division,” and it is essential to differentiate between “Bens Próprios” (Separate Property) and “Bens Comuns” (Common Property). This distinction is key in divorce proceedings, affecting how assets and liabilities are distributed between parties.

Understanding “Cessão do Poder Paternal” (Waiver of Parental Authority) is also essential for English translators. In specific circumstances, one parent may forgo certain rights, subject to legal approval. Ensuring this term is rendered accurately in translation ensures that the legal intent and consequences are clear.

Thus, in translating terms related to “Processo de Inventário” (Probate Process) and “Partilha Pós-Morte” (Post-Mortem Division), the translator should recognize the difference in English terminology and legal procedure. The accurate portrayal of how assets are managed and divided upon one’s death versus during separation or divorce is crucial.

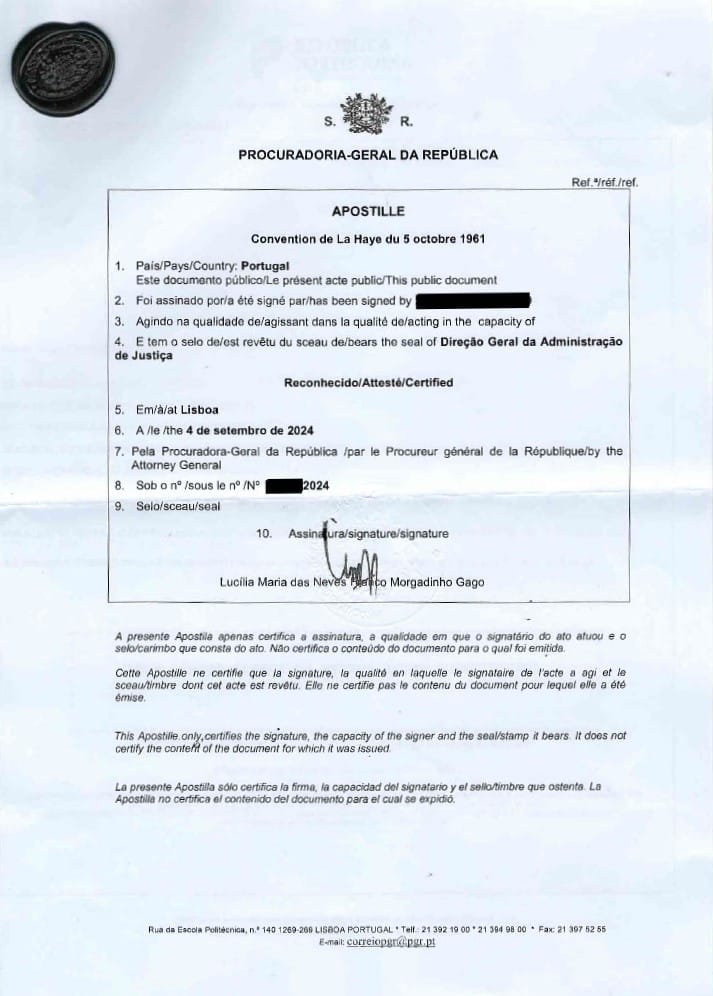

Finally, “Homologação de Sentença Estrangeira” stands for “Recognition of Foreign Judgments.” This term becomes relevant as divorce decrees obtained abroad often require validation by Portuguese courts to enforce rights concerning custody, support, and property within Portugal. Understanding this cross-border legal nuance helps in producing translations that adequately inform international clients of their legal standing.

In conclusion, translating Portuguese divorce terms into English with precision requires a comprehensive understanding beyond the lexical level. It involves grasping the intricate legal, cultural, and emotional contexts encapsulated within each term. As cross-linguistic legal challenges persist, these insights aid translators in fostering clear, accurate, and effective communication across jurisdictions.